Share this article

WSB: In eating game meat, it’s all about sharing

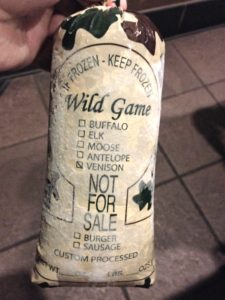

Most Michigan residents have tried game meat, a recent survey found, and those who haven’t often said it was because they never got the chance. Since game meat can’t be sold legally in the United States, access comes down to being a hunter or knowing someone who is, researchers found.

“These small acts of sharing that hunters do every year is really how wildlife meat is distributed in the United States,” said Amber Goguen, a PhD candidate in human dimensions of wildlife management at Michigan State University.

Goguen and her supervisor Shawn Riley wanted to learn more about how game meat moved around the state and how many people had tried it. They found the number of people who benefit from hunting is much larger than those who actually hunt. Seventy-five percent of respondents said they had tried game meat, including 59% of nonhunters.

Moose (Alces alces) with mushrooms and berries. Credit: Amber Goguen

The state of Michigan conducts annual phone surveys of residents, often asking them political polling questions, but researchers can sometimes tag on extra questions. In the 2014 survey, Goguen and Riley added questions about game meat consumption. They analyzed 983 surveys, and reported the results in a study published recently in the Wildlife Society Bulletin.

Respondents reported consuming 33 different species of game, including foxes, snakes, frogs and even skunks. By far the most popular game was deer — 96% of those who had tried game meat had eaten venison. Some 2% said they’d tried feral swine (Sus scrofa) — an invasive species.

People who said they had never tried game meat mostly said they hadn’t had the chance — likely because they lacked connections with people who had harvested it. Others said they thought the taste or smell would be bad. Five percent said they were against hunting and 2% said they hadn’t tried it due to ethical or moral concerns.

“The number one response we got is that they just never had the opportunity to try it,” said Goguen. “If you don’t know a hunter, it’s pretty hard to get access to wildlife meat.”

The results showed a demographic divide, with rural white men having the greatest access to game meat. “Basically, it turns out that social networks play a really big role in social distribution of wildlife meat because there is no legal market,” Goguen said.

Game meat like venison cannot be sold in the United States.

Credit: Amber Goguen

Controlling for the differences in access, researchers found women were just as likely as men to eat game.

Despite specifically being asked to report only about game meat from hunting, Goguen said, many still mentioned that they’d tried wild-caught fish, suggesting the general public and wildlife managers may have different ideas about the definition of game meat.

Since the survey took place before chronic wasting disease made inroads into Michigan’s deer population, she said, repeating it could help show if the disease has impacted deer consumption.

Identifying the way wild meat moves in the U.S. is also important considering the potential spread of contaminants and zoonotic diseases, Goguen said.

This article features research that was published in a TWS peer-reviewed journal. Individual online access to all TWS journal articles is a benefit of membership. Join TWS now to read the latest in wildlife research.

Header Image:

Researchers found that 75% of people surveyed in Michigan had tried game meat in the past year.

Credit: Christian Collins